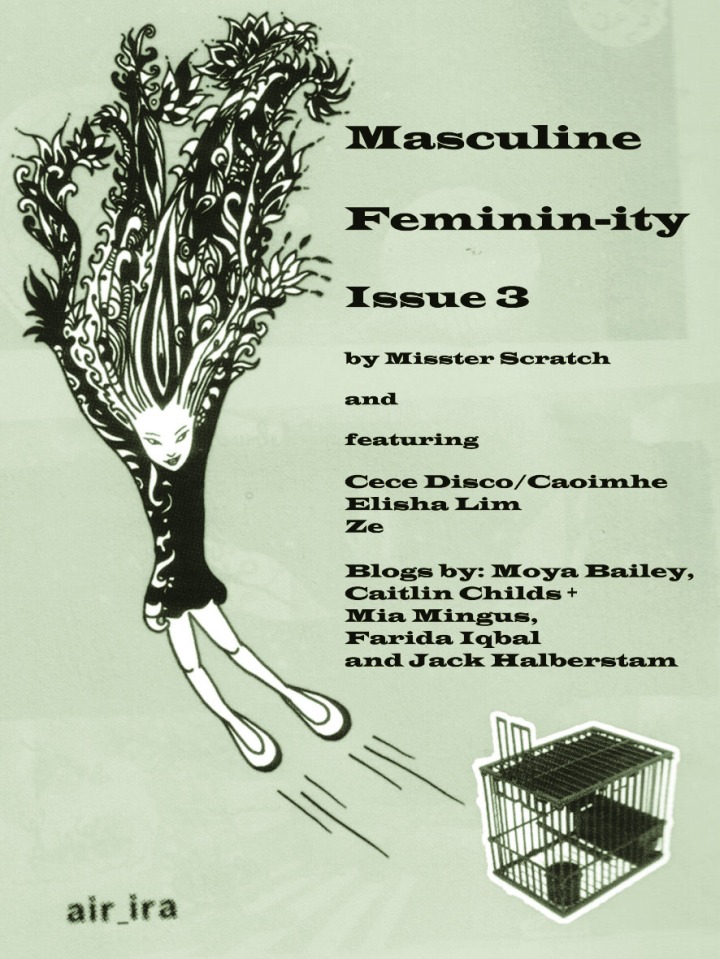

Issue 6

……………………………………………………………………….

……………………………………………………………………….

controlled

You me and Buddha

what else you could do

You thought a girl is just this….

Wind

What is she

female

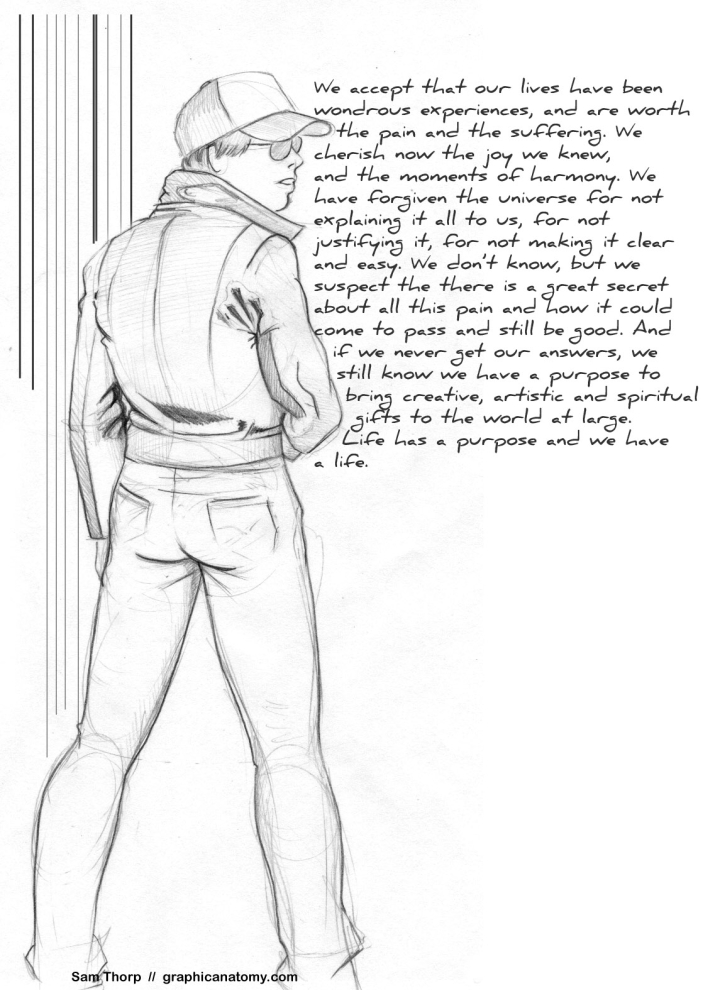

Beauty and the Beast

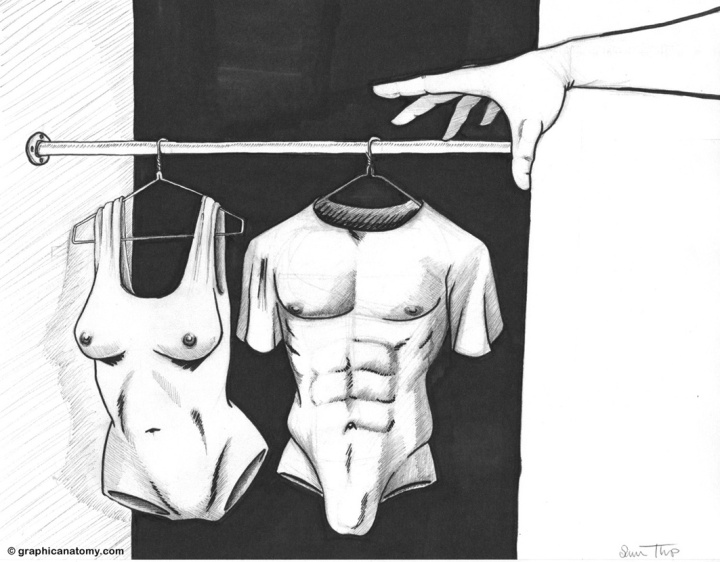

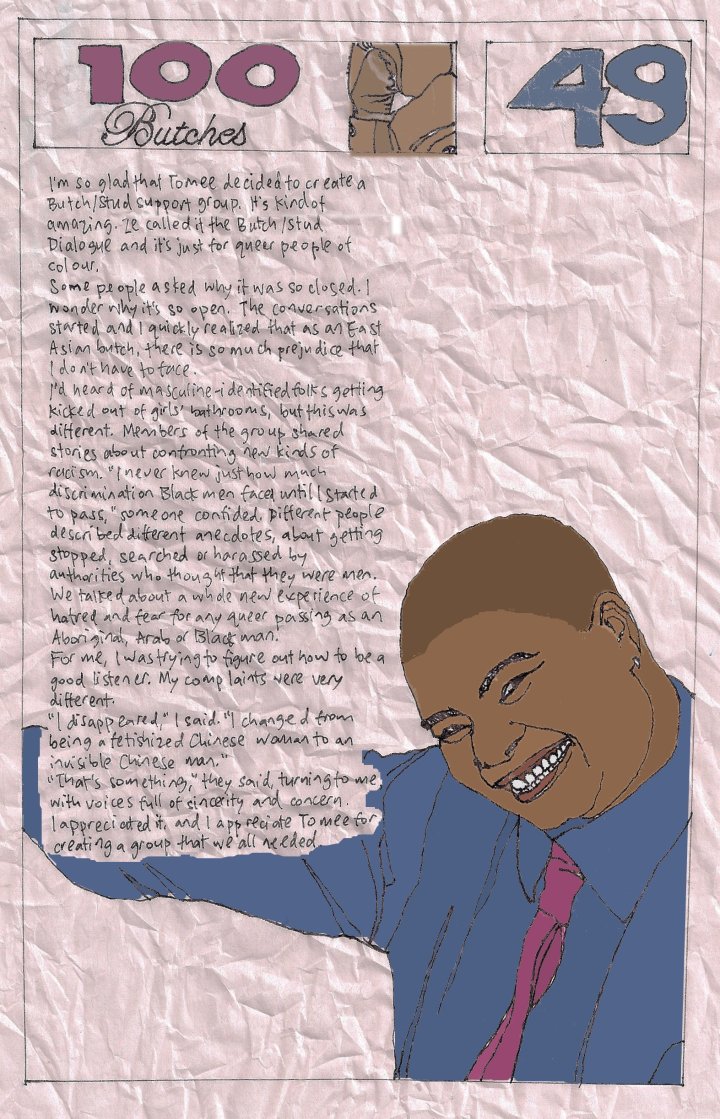

The line drawings by Living Smile Vidya are from a feminist trans perspective and self reflexively evoke her relationship with her body. Most of the drawings are grotesque, yet comical. The internal is externalized and vice versa. For instance, in her piece, ‘The Beast in Me’, the thorns/ tendrils push from the inside, till the lines between internal and external get blurred. The imagined or imaginary body is posited against the real to poignantly evoke a trans narrative. The womb that is not a womb, expels and contains at the same time. The prominent eye in the drawing stares back at the onlooker , as if to challenge the dehumanizing stares that we are subjected to. The dichotomies of good/evil, internal/external, imagine/real, woman/man is what she tries to challenge through her work.

Feminism is a core part of her work. She challenges the ubiquitous control of women by dominant masculinity and patriarchy in her piece ‘Controlled’. In ‘Female Power’ , the Rapunzel–like locks of the woman metamorphosizes into the barks of a tree that are entwined like braids. This woman, unlike Rapunzel is not waiting for a prince to rescue or release her. She is the omnipotent life giver who can destroy with her gnarled fingers just as she nourishes life. ‘What Else Could You do’, sharply critiques the entrapment and harassment women face in patriarchal society. ‘ You thought a girl was just this’ critiques the patriarchal, sexual violence by men who point their fingers/dicks at women thinking she is only a receiver for sexual acts/violence. A critique of women who are seen only as reproductive machines to be used for production of more labour force/ patriarchy is presented here. In “Passage to Genderland’, the physical transition of a trans person is likened to the transformation of a caterpillar to a butterfly.

The body is the site of struggle in all these feminist trans perspectives and a reclamation of the same is crucial to trans people, to live with dignity and self respect. Smiley is a follower of Thanthai Periyar and believes in the annihilation of caste, gender and other inequalities and her work , whether it is theatre or art, is a reflection of her militant politics.

(Trans)gender and caste: lived experience –

Transphobia as a form of Brahminism

This is the transcript of a conversation between dalit transgender feminist writer and theater artist Living Smile Vidya, who lives and works in Chennai, with her transgender brothers Kaveri Karthik and Gee Ameena Suleiman from Bangalore. This conversation took place on a late night after 11 pm in the basti where Kaveri and Gee live, following a day-long discussion between the transgender men and intergenders and lesbian community of Bangalore with a group of visiting dalit activists and intellectuals from Tamil Nadu. After the other women in the basti left the common space on the footpath and went to sleep, the following conversation unfolded:

Kaveri: “Can you tell us a little bit about gender and caste dynamics in your own life while growing up?

Living Smile Vidya: Actually, though we settled in Chennai, we belong to the Arundhati caste in Andhra Pradesh and migrated from there a few generations ago. Our caste is the lowest of the dalits because occupationally we did manual scavenging. So, my mother would have a job everyday doing street cleaning as a government worker, and then do domestic work on the side, in several houses for a couple days of the week each. 50% of her earnings would go to her husband. She had to do both house work in our own house as well as work in many jobs outside to make ends meet. My father was an alcoholic and his income contribution to the family was only 40%. But since he had physical control over her income also, I would have to get my school fees from him, though it was actually my mother’s earnings. My father would drink and physically and verbally abuse my mother and the rest of us. The whole colony knew about this because the houses are close by and small. In big houses belonging to savarnas[1] also, women suffer but that cannot be seen or heard by us because it happens in the privacy of the thick walls of their house. But at least you can hear dalit women shouting back, threatening to hit their drunk husbands etc when these fights happen in our colonies which most of the modest, “good wives” of upper/middle caste families cannot even imagine doing.

Kaveri: What has your experience of caste been when you were young?

Living Smile Vidya: “Food in urban areas for my mother who worked as a domestic worker would be served in a simple leaf. So that she doesn’t eat in their vessels.”

Gee: “But she can clean the vessels for them and then she can touch them, right”?

Living Smile Vidya: “Yes, That is not seen as touching by a dalit. Because then, who will do all their household work? My relatives in the rural areas were coolie workers (manual laborers) and for them, the owners pour the coffee from a great height into coconut shells. This also would be done only outside their houses so that nothing spills on the floor. If there are washed clothes in these houses, we can’t push them aside, can only move around them or bend under them to walk so as to not touch them. Sometimes, when visiting, I would walk from 1 dalit compound to the other which was separated by savarna colony. To go between houses you had to walk all the way around to avoid these house compounds and their lands, because they would yell if you walk near their property. Even in urban areas you find that dalit colonies will be pushed to the outskirts of the city but the major portion of the work in the cities is done by them. Untouchability is practiced in urban areas also, but the forms are less direct sometimes than in rural areas.

Gee: “I have heard that earlier in Kerala, even the shadow of dalits should not fall in the way of the upper castes. Dalits had to move backwards wiping their footprints if an upper caste had to walk the same path.

Living Smile Vidya: “Yes and before my time even the mundaani of women [upper cloth across chest] would have to be removed when upper castes came across you on the path. There was a big protest that happened over this issue in Tamil Nadu – ThoL seelai porattum – and then this practice stopped before my generation.

Kaveri: Yes, a friend Gangatharan told me about this ThoL seelai porattum, this struggle which he said started among Nadars[2] Travancore[3] against the practice of OBC[4] women being forced to not cover their chests in the presence of the savarnas. There were also severe atrocities against dalit and obc women such as assault and mutilation of their breasts which this protest struggled against, as it spread around Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Kaveri: Did your experience being raised as a child who was considered male by the family and brought up as a boy, but identifying and later living as a woman give you a heightened sense of the privileges given to men over women? For example, the first time I wore men’s clothes and walked down the street, I realized ways in which I was oppressed as a woman that were invisible to me when the world looked at me and saw a woman. I realized suddenly I could actually look around at eye level, without lewd stares from men or disapproving stares from older people – and I realized the social pressure on women to look at the ground as they walked – something I knew in the back of my head but hadn’t realized the full extent of until I dressed in men’s clothes and was liberated from it. It sharpened my feminism. In a similar way for you, seeing both male privilege from society and identifying with women and later living as a woman and facing the dangers of being a woman and a Trans person, can you talk about the way this journey has shaped your understanding of gender oppression?

Living Smile Vidya: I was a woman in my heart as a child, even as I was being given male privilege. I hated it because I dearly loved my sisters and mothers [my biological mother as well as stepmother]. I identified with them and was so angry that my sisters didn’t get the same things as me. I was mistaken to be male and couldn’t yet articulate that I was a girl and so I was educated much more than my sisters. I still always believed my older sister was very smart, smarter than me, and her life would be very different now if she had been educated. She is doing the same work as my mother only because she was born a biological woman and similar to my mother is the backbone of the household. But from the beginning I was able to influence my stepmother to be different and so her daughter – my sister, is now studying final year B.C.A[5]. This makes me very happy as despite being female born, she has joined the first generation of our family getting educated along with me.

In the beginning, I was thinking, I should act in a way that everyone will recognize that I am a woman. I was very shy, like the way people expect girls to be. I would dress very modestly, etc. Even then, as a child I would dream of myself as a saree wearing, sword yielding, woman. Like of the kind that Bharatiyar described in his writings. Bharatiyaar was a Brahminical feminist, but still, at that time, I wanted to be like that. Bharatiyar was like the Tagore of Tamil literature, a great writer, poet, musician, well-versed in many languages, and a radical thinker, part of the independence struggle and very strongly against caste and gender oppression. We read Bharatiyar at school and college, but having read so much of his work, I can still feel some remnants of his Brahminism – for example, he fought caste by performing the upanayanam[6], the sacred thread ceremony, on a young dalit boy to “convert” him into a Brahmin, instead of fighting Brahminism altogether. Similarly his vision of a woman was as an embodiment of Shakti[7], and at first I wanted to be this kind of woman.

Later I realized that since all women get oppressed under patriarchy, and trans women and dalit women through the combined might of patriarchy with casteism and transphobia, I might as well have a loud mouth and be assertive than take everything silently – to be a strong but silent woman was not enough. I decided that I do not want to be modest and soft spoken to please others or to fit the ideal of a “good woman”.

Kaveri: How did your Sex Reassignment Surgery a few years ago change your feelings on this? Many transgender people have spoken of their struggle against the gender they are brought up in, and many transgender women are agonized by the pressure on the one hand to behave in a way that is clearly socially recognized as female, while feeling outraged at the way women are treated and expected to behave – basically the double pressures that come from transphobia due to being perceived as a transgender, and male chauvinism from being perceived as women. Some have said that only after their sex reassignment surgery when their bodies were universally recognized as female in the public realm, the pressure to assert their femininity decreases and they can react to the oppression of being a woman. What was your experience?

Living Smile Vidya: Before my nirvana [sex change operation] I was definitely anxious to prove my femininity. I had a lot of these thoughts about the injustice of the oppression against women and transgenders but I was struggling from day to day to just get enough food to eat, to eat as little as possible so I could save anything extra I made from begging. I couldn’t be active on fighting for anything but survival. After my nirvana, I felt physically like a woman and then, it became easier for me to survive and to start to question my own model of femininity. With age also, my understanding of these things improved and I began to question femininity and masculinity and fixed gendered roles and behaviours more strongly.

Kaveri: Can you compare caste discrimination and transgender discrimination, for example with respect to being forced into some occupations like manual scavenging for dalit communities or begging and sex work for transgenders. How similar or different are they and what has your experience of this been?

Living Smile Vidya: Transgender discrimination is more severe, I feel, than dalit experience in urban areas. On the one hand, transgenders can only get homes in dalit bastis[8] as these are the only places where we can get any acceptance – but we usually have to pay higher rent than others. It hurts a bit when dalits discriminate, even though they discriminate less than savarnas – as it feels like my own people shouldn’t discriminate against me at all due to our shared understanding of oppression as dalit. It is paradoxical for me to face added social disadvantage as a transgender. I feel like oppressed groups should try to understand each other’s pain and work together.

Hijras or tirunangais as we prefer to be called in Tamil Nadu, at least have a community traditionally with an entire system of support [though at times, even the guru-chela system[9] is oppressive and exploitative]. We can go to shops and ask for money. Female to male trans people on the other hand, also known as tirunambi, can’t ask for money in public and do not have this traditional community.

I feel like transgenders who are working class have no dignity of labour because socially they are allowed to only beg or do sex work. But some dalit groups have taken back dignity of labour by assertions from within the community. Like daily wage labourers in agriculture can at least assert that they are making food with their own hands for the whole country to eat or artisans can claim the status of artists, but not transgenders yet. We are reduced to the status of just beggars or sex workers. This is similar to what some dalit groups have faced as manual scavengers. This occupational fixity in both dalit and transgender communities, is done by closing off alternative options. Thus, manual scavenging becomes an occupation enforced on dalits through the exclusion of access to other jobs; in a similar way begging and sex work are forced occupations for transgenders through exclusion from other jobs. But in spite of this, we retain some of our dignity in the face of this exclusion.

To retain dignity we have to think these jobs are normal. Manual scavenging and begging just becomes like a practice. Children are mentally prepared by society to think it is normal. In school when they would ask, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” We dalits wouldn’t say doctor, engineer, but our boys would say for example, “I will work in a cracker factory”. Girls would smile and not respond. Dalits are socially conditioned to internalise that they are meant to do only some jobs and don’t dream to do anything else or get the access to education and alternative jobs. Transgenders also when they first realize that they are trans women, they immediately think they will have to beg, because they see transgenders only in one place – begging on the street. So, by repetition historically and by not providing alternative options, these jobs become fixed. Amongst dalits with reservation, some changes have happened in the sense that access to educational facilities have opened up a bit but numerous other ways are used to torture us till we drop out or commit suicide or fail. Even in reservations, it is not the lowest of the dalits like us who benefit, but the more elite. This is somewhat like the savarna transgenders who have NGO funding claiming to represent the community and getting all the benefits. This kind of representational politics gives a false picture of progress of these communities from this funding model.

Kaveri: Is transgender a kind of caste? The Backward Classes Commission under C.S Dwarakanath[10] has recommended that transgenders be included as OBCs for reservation. What do you think about this?

Living Smile Vidya: We need reservation on the basis of gender, not caste. But it has to be more complex. But I definitely do not want to be OBC. And you will understand why as a dalit, I do not want to come under the OBC category of all things! Putting transgenders under an oppressed caste category erases the caste privileges that savarna transgenders have. It is better for us to have caste and gender based reservation so that dalit women and dalit transgenders get representation. Otherwise reservation will only benefit savarna transgenders and dalit men.

Kaveri: Is there caste within the transgender community? Do people lose caste as they enter hijra system?

Living Smile Vidya: There is not so much caste in the hijra community because everyone’s names are changed. As you enter the hijra community, you lose location, language, last name. A few members of the transgender community who are dalit have figured out I am dalit and have secretly told only me because they knew I’m dalit. They have also told me not to talk about eating beef so that no one in the transgender community figures out I am dalit. Some castes though are very proud, such as Thevars[11] and Pillaimars[12], who are always proudly asserting their caste. I have seen some kothis[13] and hijras[14] and say things like, “I might be a transgender like you, but I am a Thevar in the village”.

Even I have once pretended to be Thevar when I was confronted by an auto driver for smoking and it was a dangerous situation. I was taking his auto late at night. I saw the picture of a Thevar leader Muthuramalingam Thevar in the auto, so I put on a Madurai accent and pretended to be a Thevar girl to save my skin. He was so impressed he asked if could ask my father for my hand in marriage! [Laughs]. There I was, a dalit, transgender woman passing off as an upper caste biological woman to save my skin and getting a marriage proposal at 2 A.M!

Gee: When you go for a jamaat[15] or some such ceremony in the hijra community, if you even touch a senior hijra’s saree accidentally, you have to pay a fine. Of course this is not a caste practice as it happens if any hijra touches any senior hijra’s clothes, but do you think this practice has come from caste untouchability?

Living Smile Vidya: It is like class, it’s showing respect. It’s not outlawed, but punished with a fine. Since we get no respect outside the community, the elder tirunangais say they have made some rules within like this to get respect with increasing seniority. When I was a younger kothi, I would respect all these traditions but then I found them oppressive and too hierarchical. It is like how victims in some respects become oppressors when they get the opportunity or power. I don’t know where this particular association of not touching means respect comes from. You may be right in guessing that it comes from caste practice.

Gee: “Can you talk a bit about how migration plays a crucial role in our search for freedom whether it is as a dalit or as a transperson. For example, I read in Omprakash Valmiki’s[16] autobiography how he says that when he migrated from his village, he could “pass” as a non dalit. Similarly, we know that all of us as transpeople, move out of our native towns to find freedom and also “pass” more as women or men”.

Kaveri: As someone who could pass as a non-dalit, non-trans woman, how you tell other transpeople or dalits that you are one of them. How do you “out” yourself to them?

Living Smile Vidya: One’s recognition as dalit or transgender within the village gets removed by migration, but some of the markers still remain. Outing oneself as transgender really depends on how you talk, how you walk. I “pass” most of the time in public as a woman. So, if I want to tell another kothi/hijra that I am also a trans woman, I use our own kothi language to give myself away as one of them. As to outing oneself as dalit, the markers are where you live, how you speak- the dialect, last name etc.

From my experience, it is only non dalits who ask what your caste is. Dalits always know their brothers or sisters when they see us. When I want to find out if someone is a dalit comrade, I just ask a common dalit friend. But mostly, when we speak about dalit issues, we can tell if they are dalit or not. Because of sub castes and feeling of superiority, I am sometimes scared of outing myself as belonging to the arundhathiyar caste [manual scavenging]. There is some discrimination even between different types of dalits. The adi dravida castes are considered superior to us and so even at home, my parents never allowed me to learn my mother tongue, Telugu, because they were afraid that the general public would figure out and discriminate extra against me. But because living spaces are so segregated on the basis of caste, it is easy to know who the dalits are in the village. Among the dalits, the Telugu speakers would be clearly identified as the so-called lowest dalit castes. I never hide from other dalits the fact that I am also a dalit, even if I don’t reveal my sub caste. Similarly, I never hide to other trans women that I am also one of them.

Kaveri: What do you tell your dalit comrades when you attempt to unify the transgender and dalit struggles?

Living Smile Vidya: I try to explain that they have also been made to feel less human by savarna castes, in a way similar to how society treats tirunangais. I ask them why they can’t understand our pain when they have had similar experiences individually and historically. When they ask me, “Why do transgenders beg and not work? You will get more respect if you just work like other people”. I say, “Why don’t dalits become bankers, doctors, engineers. Why are they still stuck in the same jobs after all these years? Is it because we dalits are not capable? Or because we are lazy and don’t want those jobs? Actually it is because of lack of opportunity and discrimination. The same goes for transgenders. If you offer transgenders jobs, they will stop begging and work hard and live with dignity like others in society. Begging itself is very hard work”. Dalit comrades need to fight patriarchy and transphobia along with casteism.

Transphobia is a type of brahminism. It gives us no other option but to do “dirty” jobs like sex work and begging and then calls us “dirty”, just like caste system did with dalits. When I draw parallels like that, my dalit comrades understand better and work with me.

Kaveri: What do you think about unifying the oppressed peoples’ struggles?

Living Smile Vidya: If I give a talk on, transgender issues, I tell people they have to join with our struggle if they believe in social justice. I always talk about working together, along with women’s struggle. But I know that most so called feminists think that I am a man in woman’s clothing. They would treat me as if I am not quite a woman. The general public accepts me as a transgender quite readily so why do activists take longer? Some of these feminists will wear fabindia[17] clothes and their gold and think women must be modest. They talk as if the strongest and most satisfying thing in the world is to give birth and take care of their children. As a trans woman, though the fact that I cannot have biological children, is used against me to make me feel less like a “real” woman, I sometimes feel grateful that I have been spared being thought of just as a baby producing machine! They also are very patronizing about caste and can talk progressively but will have a dalit woman making tea and serving them at their meetings instead of also including her and learning from her experiences. Dalit movements also have to be worked with internally, so that their perspective on gender broadens. In another way, savarna feminists should broaden their perspective to include trans women and also work really hard to lose their caste bias. But ultimately we have to understand that we are all people under attack whether the enemies are Brahmanism and caste, gender oppression, patriarchy, NGOs, the State, capitalism, multinational companies, Western neo imperialism etc. We must all unify to fight an effective struggle against these monsters.

[1] Savarna is used to refer to people born into castes that are considered to be “upper” as opposed to “lower”. Historically these castes have exploited the “lower castes”/dalits economically, sexually, socially and politically.

[2] An assortment of sub castes in Tamil Nadu that are categorized as Other Backward Classes [OBC]

[3] Now called Trivandrum or Thiruvananthapuram located in the state of Kerala. The Kingdom of Travancore at its peak comprised most of modern day southern Kerala, Kanyakumari district, and the southernmost parts of Tamil Nadu.

[4] The Central Government of India classifies some of its citizens based on their social condition as Scheduled Caste (SC), Scheduled Tribe (ST), and Other Backward Class (OBC). There is at present some affirmative action for improving the social and economic condition of OBCs. For example, the OBCs are entitled to 27% reservations in public sector employment and higher education. In the constitution, OBCs are described as “socially and educationally backward classes”, and the government is enjoined to ensure their social and educational development. The dalits/ Scheduled castes have a contentious relationship with OBCs as the graded system of caste hierarchy places SCs below the OBCs in the hierarchy but the OBCs also benefit from affirmative action. In the recent past, atrocities on dalit communities have been perpetrated by OBCs as a possible effect of the newly found upward mobility amongst dalits which hurts the caste pride of OBCs.

[5] Bachelor of Computer Applications

[6] Refers to the ceremony of doing puja and tying the “sacred thread” of caste purity on a Brahmin boy. Here, instead of rejecting it altogether as Brahmanical, Bharatiyar tries to invert it by performing it for a dalit boy. Smiley is critical of this act of attempted subversion.

[7] Shakti is the concept, or personification, of divine feminine creative power, sometimes referred to as ‘The Great Divine Mother‘ in Brahmanical Hinduism.

[8] Slums

[9] Guru- chela system is one in which the senior hijra adopts a young hijra as her daughter and becomes her mother. Traditionally, the young hijra has to serve her mother like a dutiful daughter , give her half her earnings and look after her house. In return for which her mother will give her protection and also facilitate her sex change if it is to be done traditionally and outside the medical system. Though hierarchical in nature, it is a culturally created system of alternative familial relations and support.

[10] For the first time in India, the Karnataka State Backward Classes Commission recommended inclusion of transgender community in the OBC list under the name “Mangalamukhi” and inclusion of children of sex workers and HIV positive people under the name “Sankula”. C S Dwarakanath was the Chairman of the Commission. Though the recommendations were given over one and a half years back, none of the recommendations have been implemented yet.

[11] Thevar (Derived from Sanskrit Devar) means God. In the early days, Kings were portrayed as god and called as Devar. Devar is not a caste name but a surname used by Mukkulathors, a dominant caste in Tamilnadu.

[12] Pillai, Pillay, Pulle, Pilli or Pillaimars is an “upper” caste title used by land owning caste of Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

[13] Kothis are female indentified trans people who may or may not choose to undergo sex change operations/ dress in what is considered to be women’s clothing. Kothis can join the hijra system but respect for post-op transwomen is greater in most hijra communities.

[14] Hijra derived from Persian word “ezra” meaning “wanderer”, is a term used for transgender women in India. Most hijras are post-op and live in hijra houses. Hijras used to serve in the courts of the Mughal emperors as attendants of the queen. Culturally and religiously they have some amount of sanction as people fear the curse of a hijra on a new born baby and she blesses the child in return for money. Hijras also dance at weddings for which they are paid. Apart from this, begging and sex work are the main occupations and they face a lot of phobia, discrimination and violence from their families and society at large.

[15] A jamaat is the legal system developed by hijra communities to resolve conflicts and to mete out punishment to wrong doers. Senior hijra Gurus are the decision makers in these functions and there are strict codes of conduct that hijras should follow when attending jamaat.

[16] Valmiki, a leading Hindi Dalit writer and author of the celebrated autobiography Joothan (1997) has published three collection of poetry – Sadiyon Ka Santaap(1989) Bas! Bahut Ho Chuka (1997), and Ab Aur Nahin (2009); and two collections of short stories – Salaam (2000),and Ghuspethiye (2004). He has also written Dalit Saahity Ka Saundaryshaastr (2001), and a history of the Valmiki community, Safai Devata (2009).

[17] A chain of ethnic, “Indian” clothes worn by most well to do civil society activists and feminists.

Living Smile Vidya, was born to Veerammal R on 25th March 1982 ,in Trichy, Tamil Nadu. She identifies as a dalit transwoman artist. She is a professional theatre actor and has worked with more than nine renowned directors in theatre. She has worked in Tamil and Malayalam movies as assistant Director. Living Smiley Vidya has written her critically acclaimed autobiography “I am Vidya” which has been translated into English, Malyalam, Marathi and Kannada. She started doing line drawings in 2010 and has received no formal training in arts.

……………………………………………………………………….

Little Samo Bunny

……………………………………………………………………….

but you’re only the undertaker

because entertainment media is the fanciest graveyard.

they need to shut up because people

are killing to be buried here.

after all

you bury your queers because you love them

it’s not like you bury them because you’re fucking frightened

it’s not like you murder your darlings because you are terrified

they’ll conspire with your readers and plot the death of the author.

maybe you bury your queers as to grant no one any incentive

lest your actors be unshackled from your offered arcadia

lest they go mad and film their own unlicensed pornographies

that violate your copyrights of your queers buried between your frames.

and when you bury your queers between the pages

blame the bigotry of your editor

who will blame the bigotry of the publishers

who will blame an irate imaginary audience

and all of you will blame an indifferent imaginary public.

introspection is too close to breaking into graves

so just bury the queers down there

with the skeleton service.

the skeleton service is all i know

it pours me my drinks

we speak about the myth of mirrors

we speak about stripping ourselves down to the bones

(you unbury us when you need shambling contradictions

you unbury us to craft villains and frankensteins)

first they are saints and then they are exhumed for parts.

you bury mad men

the way you bury martyrs

we turn to dust and

dust buries the invisible.

you don’t have to suffer guilt

you’re only the undertaker

there’s a reason you don’t check for a pulse first.

(if all else fails bury them in ennui

bury them in uninspiration

bury them fettered to a story so insipid

no one answers the chimes in the graveyard shift)

i’m tired of graverobbing in the deserts of your narratives

i’m tired of unearthing tombs that tell me everything

you think i should know:

that i am irrelevant

Ashwin Shakti is an artist and poet. He lives in Chennai India. Check out his work at www.auctoricide.com

……………………………………………………………………….

intergenerational time travel interview:

trans masculine-femme brown bears on healing justice

with raju rage and mîran n.

This interview is also published with “Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung” http://migration-boell.de/web/diversity/48_3638.asp

This kitchen table discussion between two trans masculine-femme brown bears (of colour) models healing justice through non-academic personal/political narratives. This interview uses imaginative time travel dialogue as a tool for empowerment. Mîran and Raju talk to each other and their younger selves to create a transformative discussion about what it means to be us: trans people of colour in a world full of struggle and survival. This project embodies healing justice as a way through oppression, for our current and younger trans of colour selves.

Raju: I really like this idea of doing this actually-at-a-kitchen-table informal interview as a form of empowerment and healing. I had originally been suggested a similar idea by my therapist and was reluctant to do it in front of someone without the life experience to understand what it means to be trans and a survivor. But with you, I can’t think of a better person to do this with and I think the time is also right for this.

Mîran: First of all, I want to thank our friend Jin Haritaworn for connecting us with this publishing opportunity. I was having dinner with you, Raju, and told you about my spoken-word-piece- -which-is-still-not-done-and-god-knows-when-will-be, where I, as my adult self today, write a letter to my younger self. My therapist also suggested I work with my inner child, but I don’t know if I, as a queer, trans, working class, fat poc with health struggles, want to talk about such intimate things with my white, abled-bodied, upper class therapist. I’m glad we realized this was something we are both interested in and want to work on together.

Raju: Yeah, that makes sense. So often we don’t have places to really voice how we feel because we are told we are ‘crazy’, paranoid or too angry, so we just end up shutting up and sometimes even shut down. It can start to feel stressful and uncomfortable to discuss the oppressions of being brown and trans, and so I like how this organically happened. I guess we have, from our many conversations before, shared our very similar backgrounds and upbringing, and so it makes sense that this would work for us as something that we would both find empowering and have both thought about. I see our conversations as a community collective therapy already anyway, and feel safe to discuss this with you. I feel it would be a great exercise for each of us personally, and hopefully, something that other (trans/ gender nonconforming) people of colour of all ages could also get something from? I hope so. Plus, I like time travelling. 😉

Mîran: Speaking of silence and paranoia, I think paranoia often protects us. Since as queer/trans of colour people, we don’t have many spaces in which we can safely exist, or just relax and be ourselves. We have to make compromises every day, just to survive. That’s why I think it’s important to see this interview as a space to share something that we would normally not be able to share, because we don’t have the privilege to find each other easily, because we don’t live on the same continent, borders separate us, we don’t have the finances and many other reasons… Lets begin!

Younger Mîran interviews Raju:

Mîran: So I would like to start with my younger self asking you questions about me today.

Younger Mîran: How do I look?

Raju: You are handsome, Mîran [adult Mîran laughs out], you always have good hair and you talk about it ALOT,haha, but you have the best hat collection even though you don’t need it. Over time I have seen you become more comfortable with yourself.

Younger Mîran: Why do you call me Mîran? Do I have long or short hair?

Raju: Your hair is short. Right now you shaved it and its growing out, but when it is a bit longer it looks really really good. Your name is Mîran because you chose that name for yourself. I also chose my own name and it’s different from my younger name.

Younger Mîran: That’s so cool! I always wanted short hair but my mother never allowed it. She said I wouldn’t look like a girl anymore. But I never really cared about looking like a girl or a boy. I don’t understand what she is talking about. And I like the name Mîran!

Raju: When I was younger I felt similar to you. I had shorter hair but never in the style I wanted it, and my parents always encouraged me to style it and make it feminine, especially as I got older, but I did have it short. When I was 18, I left home and I cut it real short and felt so good! When you are 20 you will also do that, you will shave your head, too!

Younger Mîran: I will? Wow!!! And where do I live?

Raju: You live in Berlin.

Younger Mîran: What?! Berlin? Really?

Raju: YES! And you live on your own in your own apartment. It’s really nice and I have stayed there sometimes. There are pictures of you there that I have seen.

Younger Mîran: I’m cute, right? 🙂 Wow, my own place. I can’t believe that. I thought that I will always live in Remscheid, study here, and probably marry someone.

Raju: Well you have lived in Berlin for a few years.

Younger Mîran: Really?!! Wow! …but, Raju, can I tell you something? But don’t tell my parents.

Raju: Of course.

Younger Mîran: Sometimes I don’t feel comfortable in my body or I imagine myself differently. Yesterday, I was playing soccer with boys and it was really warm out, so I unbuttoned my shirt like them and they yelled at me. I think I like air on my chest but I also wanna cover it sometimes. Also I like longer hair and I wanna put make up on, but not all the time. It’s confusing.

Raju: I felt similar when I was growing up. I also played with boys when I was younger, but I knew I was different in some way and also confused about that. I was sure about being masculine, but knew I was born female. I felt comfortable being masculine and didn’t even really question it, but friends and family had an issue with it. I felt that I wanted to be in a male body if I could choose that, but knew I wasn’t, and I wasn’t like the other ‘tomboy’ girls who still wanted to be girls. I also liked being feminine when I was younger but wanted to be able to decide and choose and do it when and how I wanted to. So, I liked to be masculine and feminine but it took a while to realise that was ok. I think your gender will always affect other people, and other people always want you to be what they want you to be, and see what they want to see. The main thing is being comfortable in yourself. That’s easy to say sometimes and in reality it is difficult when people make fun of you and tell you that you should look and act a certain way, and when there is also racism on top of that. I think those people are also struggling with their own gender. It may make it easier to realise that?

Younger Mîran: Thank you for saying that, Raju. I think that is the answer to my problem. I don’t have a problem with how I look or what I wear. Other people make me feel uncomfortable.

Raju: So Mîran, how old are you? Who are your role models that you look up to? Do you have any?

Younger Mîran: I am 12. My idols are Leyla Zana and Freddy Mercury. My uncle says we like Leyla Zana because she wants to free our people. I like how she talks, she has shorter hair and she is very strong. I like Freddy Mercury because my uncle listens to his music, and I like the makeup! And the outfits! Sometimes I wish I could wear leggings and tighter things but my mother tells me I’m too fat and it doesn’t look good on me. She also says that we are migrants and attract attention anyway, so we should keep a low profile. Also, I like Prince, too.

Raju: People think it is important to fit in and not stand out. I think it is more important to be yourself. The role models you mention are also some of my role models too! And none of them seem to fit in to me, they all stand out and are very powerful people. Freddie Mercury is queer and also a person of colour and not many people realise that. He has struggled with his identity, and then Prince always gets called gay because he is feminine and he just carries on being himself. Sometimes it’s hard to be yourself because in some cases that may make it harder for you to survive. That might be why your parents say these things to you. It is hard for immigrants to survive. I was also an immigrant so I know how it feels. Tell me more about Leyla Zana as I don’t know who she is.

Younger Mîran: Leyla Zana is a Kurdish freedom fighter. She is very important and I think she is very strong. She was in prison a lot and she spoke Kurdish in the Turkish parliament, even though it was illegal, , but she doesn’t give up. And I like her hair.

Raju: Leyla Zana sounds like a very good role model. Some people are bold and daring and have the strength to fight. Sometimes you don’t always have that and that is also okay because it is a struggle. The older version of you is such a fighter!

Younger Mîran: Really?! So, what am I doing? I always wanted to be an artist.

Raju: You are doing many things. As I said, you are definitely a fighter. You stand up for your community and fight for their political issues. You are involved in a lot of anti-racist organising with other queer and trans people of colour. Do you know what queer and trans are? You and I work together on projects, too. Oh, and I forgot to say you are a dancer!

Younger Mîran: I think I understand. Queer and trans are people like you are and what I wanna be? A dancer? Wow, I hate dancing! But actually I like it but I never dare to. But sounds good! And what are people of colour?

Raju: Being of colour and using that term is empowering for us. It means we identify our selves instead of letting people tell us that we are scum and not worth anything just because we are not white and don’t look like we were born here in Europe. It is a very political term. Not everyone uses this term and may use other words to describe themselves in a similar way, but many people do. It makes us feel good about ourselves and means we discover things about ourselves that we may otherwise not.

Younger Mîran: And of colour is probably people like us? Things are unfair for us. So the other students in my class are not of colour.

Raju: Yes, exactly! It also means we can find each other and build community and chosen family. I wish my younger self could meet you. I’m sure we would be friends, just like our older selves, because we have a lot in common. Actually, we call each other brothers now and we really take care of each other!

Younger Mîran: I would like to be your friend, there are lots of things I would like to know about you! You sound really nice and I always wanted a brother! Sounds like I’m going to look like I imagine and I even have friends! Now I’m really less scared of the future.

Now the adult Mîran interviews the younger Raju.

Mîran: Hey Raju! Tell me, how old are you?

Younger Raju: Are you talking to me? My name isn’t Raju. But I like that name. One of my cousins is called Raju, too. I am 7.

Mîran: Oh, excuse me! I forgot to tell you that you chose the name Raju for yourself, recently. Is it ok if I call you Raju now?

Younger Raju: Wow, I like it! I didn’t know you could choose your own name. My parents called me a name that is very unusual and not many people here can pronounce it properly. They make it into an English name which I don’t like, and people don’t think I’m Indian because of it, so I like Raju.

Mîran: So, I’m Mîran and I am a friend of the adult person you are going to be in the future. Do you have any questions you want to ask me?

Younger Raju: Yes, I have so many questions!!!!! So, am I old? How old am I and what do I look like and what is my personality like and where do I live? And, and… how do I know you?

Mîran: Wow! So many questions! I will try to answer them all. So, you are 34 now and you are still based in London, but you lived in many other places like Vancouver and Berlin. Actually, you are going to fly to India very soon. Right now, you are in Berlin, and that’s how we met 4 years ago. You were part of a performance group and I met you and Jin at the same time. Jin is also a good friend of ours. By the way, you look fantastic! I want to look like you do! Right now you have shorter hair again but a couple of months ago your hair was longer. It’s wavy and curly. You are 5’5, very handsome and I have to tell you: great style! You always know how to look good and combine your clothes. You are very outgoing and yes, shy sometimes. You are one of the most sensitive people I know and helped me a lot when I was very confused about a lot of things, like gender. You told me it was okay however I want to look and who ever I want to be. Oh, and you are VERY smart and a great and important activist. AND a masterbaker!!!

Younger Raju: I am soooooo old! Wow, that is amazing. I could never imagine those things about myself! I am so shy I could never imagine being on a stage performing. I don’t like how I look now because people make fun of me and tell me that because i’m Asian, that is a bad way to look. Or, that I look like a boy and I should look more like a girl, so I feel ugly. I do like dressing up but I am confused about gender, I’m not sure I know what gender means. Do you mean being a girl or a boy? Because I want to be both!

Mîran: Well, that didn’t change! You still like to dress up! You like to play with looking masculine, feminine, etc… gender, basically means how you see yourself (in terms of being a boy or a girl) but that doesn’t mean it’s how people read you and it also doesn’t mean that you have to be a boy or a girl.

Younger Raju: Does that mean that I can be both? Because I sometimes think I am a boy and want a boy’s body but I don’t want to be exactly like the other boys I know. I also like dressing up and make up and jewelry, too, but people say that’s girls’ things.

Mîran: One of the cool things with growing up is that you have more freedom with choosing your surroundings. You, for example, found a community with queer and trans folks of colour, who respect who you are, how you look and what you think. I understand that it’s confusing right now, but later you will see that you don’t have to choose between boy or girl. You are great the way you are and the way you look. No matter what other people tell you, okay?

Younger Raju: That is good to hear. Nobody ever told me that before. I’m surprised to hear those things about myself.I’m also surprised that I’m going to India! Because my family were originally from India and I’m so curious about the place that my family is from. I was born in Kenya and only know about that place and I don’t like it here in England.

Mîran: I understand how you feel. When I was growing up I also never got to hear people say things like that. As brown people we grow up with a lot of white people telling us we are not smart enough, not pretty enough, not skinny enough, etc. These messages are also all over television. But you are so cool! I don’t know you as a younger person, but I know you today as an adult and you are pretty fantastic!

Younger Raju: Are you like me? Because I don’t imagine having friends who knew about me and my gender? And being my friend. It’s also not cool to be a brown person – are you brown, too? All the popular kids are white and you can’t wear Indian clothes or you get bullied. You have to fit in here, my parents tell me that, and I can see it is true, but I don’t fit in. Does that mean that the older me has friends who are like me?

Mîran: Let me tell you one thing, young sibling. It is SUPER COOL to be brown! We are actually pretty similar with the way we grew up. I am also trans and brown like you are. And yes, you have more friends like me! We have a big chosen family of queer/trans of colour folks who love you and admire you. Don’t worry about the popular kids! Later, they won’t be important. They won’t be relevant in your life. You are going to be so much more than just popular. If they were still lucky enough to know you, they would probably envy who you are and what you made out of your life.

Younger Raju: WOW! You can choose your family too!? Just like your name. That is so cool. I like that. I love my mother but I don’t like my father at all and I want to be like my brother because he is a boy and I want to be one, too. It’s so funny to hear that the future can be so different! It sounds so good! And to hear that you also had a similar life, because I feel so different to my friends now.

Mîran: Yes, from the things you told me over the years, we both had to and have to deal with white middle and upper class kids. They are so much more different from who we are and what we face in our lives. Also, those kids still exist today in our communities — the people who look down on us for being who we are — and it’s tricky to deal with, but don’t be scared, we have our own people, people who grew up like you and me and we support each other, laugh with each other and also cry with each other sometimes.

Younger Raju: But how did we find each other? I wish I could find you and the others now! I never thought about my gender but now I can see that it is something that bothers me a bit because I can see that other people aren’t like me and it makes me feel like I’m different in a bad way. I want to meet people like me. I want to meet you!

Mîran: The problem is that the world that we live in, separates us from each other and isolates us. But you are smart, you will break out of it, and find me! Very soon! Until then, you can read books by bell hooks, Audre Lorde, and other black feminists. Read about Stonewall (but not the whitewashed version) and try to find books about queer and trans of colour experiences. Maybe in a library… Another cool thing, later we will have the Internet (connecting all computers — computers are also cool! — and then you can get information with that! Oh, by the way, you also publish about these things!

There are other queer/trans people of colour who live close to you, that you don’t know yet.

Younger Raju: That sounds incredible!!!! This sounds like a sci-fi movie! I love sci-fi and I also love reading. All I am allowed to read right now is encyclopedias and educational books that help me learn English and fit in, but I want to read these instead. I’m not sure what they are or what they say, and I don’t know some of these words, queer and trans and the names of those writers, but it sounds amazing and I have a feeling that I will learn a lot! Thanks for telling me about them! I can’t wait to grow up now. I hate this place, it doesn’t feel safe and I want to leave! This makes me feel so much better to know there are these things out there and that my life will change.And it sounds like I am happy and I have a good life!

<time travel ends>

Mîran: Wow, I don’t know how you feel, Raju. But that was very intense! I feel like this was more effective than a lot of therapy sessions. It’s so healing to talk to a good friend/comrade, watch and listen to your younger self. I never would have guessed how much we can learn from our younger selves. I was too scared to publish the letter I am writing to the younger part of myself but this encourages me to do so! Thank you, Raju, for sharing this intimate piece with me. Again, I see how important it is that we listen to and write our own stories, witness our strengths and supports and heal ourselves and each other. I like kitchen table (this one literally!) discussions with my cutie poc (qtpoc) siblings! Thank you for guiding each other through the scary past. It makes it a little easier to look into the scary future. Like the Black scholar Ruthie Wilson Gilmore said, “We should plan to win. And we can win.”

Raju: I liked using this narrative form of self therapy as a way to unfold and reach out to our younger selves. I feel these conversations have been healing to a younger part of me, and also very much the older present me, who felt and often feels isolated. I also enjoyed time travelling with you and would love to do this again, maybe continually, with you and for myself as a way of healing from past trauma that we often forget about or bury deep when we get older and have too much to deal with still, and when our struggle takes over. I feel it is important to share those moments to gain strength and solidarity. I feel like this has been quite a journey from the kitchen table to the inner depths of our fragile, but strong surviving younger souls, that carries us into a less scary and more safe future! Thank you, Mîran, for sharing this with me, for carrying me and protecting me, and showing me now and infinitely, that there is always a way out and/or a way forward!

Raju Rage, being disciplined from a young age with learning English and studying, wants to be a writer and artist and have his work published one day (he will!). He hopes to be successful, handsome and grow up to be a superhero living in a hot country!

Mîran N. likes ice cream (going to suck in the future with lactose-intolerance), music and soccer. They hates spiders, aftershave and white beans (will never change). Mîran wants to be a famous artist.

………………………………………………………..……………..

21 + genders…… by Gopi Shankar

திருநர்– Transgender

1. திருநங்கை– Trans-women

2. திருநம்பி- Trans-men

பால்புதுமையர்- Genderqueer

1. பால்நடுநர்– Androgyny

2. முழுனர்– pan-gender

3. இருனர்- Bi-gender

4. திரினர்- Tri-gender

5. பாலிலி– A-gender

6. திருனடுனர்– Neutrois

7. மறுமாறிகள்– Retransitioners

8. தோற்றபாலினத்தவர்– Appearance gendered

9. முரண்திருநர்– Transbinary

10. பிறர்பால்உடையணியும்திருநர்– Transcrossdressers

11. இருமைநகர்வு– Binary’s butch

12. எதிர்பாலிலி– Fancy

13. இருமைக்குரியோர்– Epicene

14. இடைபாலினம்– Intergender

15. மாறுபக்கஆணியல்– Transmasculine

16. மாறுபக்கபெண்ணியல்– Transfeminine

17. அரைபெண்டிர்– Demi girl

18. அரையாடவர்– Demi guy

19. நம்பிஈர்ப்பனள்– Girl fags

20. நங்கைஈர்பனன்– Guy dykes

21. பால்நகர்வோர்– Genderfluid

22. ஆணியல்பெண்– Tomboy

23. பெண்ணன்– Sissy

24. இருமையின்மைஆணியல்– Non binary Butch

25. இருமையின்மைபெண்ணியல்– Non binary femme

26. பிறர்பால்உடைஅணிபவர்– Cross Dresser

“Gender” is related to physical and emotional perception of an individual. Restricting gender in the binary categories of female and male is erroneous as we have to be aware about the existence of more than twenty categories of gender. The same is also true for the sexual orientation where the dominant public knowledge is only limited to the heterosexual orientation. Here we do not want to narrow down our emphasis on homosexuality, rather here we emphasize about Gender-variants, which transcend the binary categories. Gender and sexuality are the rights of an individual and interfering to those refers to the interference in personal freedom.

In India, thanks to the colonial legacy of shallow Victorian values, we have come to see this as a deviant behaviour or violation. Indian culture is originally abundant with legends and mythologies where heroes and heroines have chosen various genders without guilt and their choices have been accepted and respected. Ironically, today the western nations are progressive in researching and educating about gender and sexuality expressions, while we, despite our rich cultural heritage respecting and accepting gender variations and choices are lagging behind and even lacking that sensitivity.

While the students of medicine, engineering, law and literature specialize to practice their own functions, what we lack is that there are no studies or synthetic discipline to study the biological, bio-ethical, legal, psychological, social dimensions of the very basic emotions concerning sexuality and gender. Though the Indian universities can offer worldwide recognized studies, we certainly lack any basic axiomatic framework pertaining to gender and sexuality, while the foreign universities have even started their own departments and research activities. The most painful condition is that even psychologists are mostly unaware of Gender-variants and their localized issues pertaining to Indian conditions.

India’s pre-colonial traditional as well as various localized folk traditions have taken a far healthier attitudes in dealing with sex-education, that may surprise many people on both sides of the fence of sex-education who want to map Indian culture with dominant Victorian male value system. Various folk deities and traditions emphasize fluid nature of gender and mythologies have stories that reinforce this idea. So a child growing up will not have a strong shock value or guilt feeling in relating to one’s own sexuality or others as gender-variants. Devi Mahatmya and Mahabharata are two such examples. Koothandavartemple festival in Tamil Nadu is another example of local folk tradition organically linked to the pan-Indian culture in dealing positively with creating awareness for and empowering gender-variants. These cultural possibilities need to be taken up and explored to create democratic social space for gender-minorities.

Hence a very comprehensive solution for this problem is the induction of social awareness starting from the school days with stories, and progressing into the high school curriculum with a biology and psychology of gender issues over the whole spectrum of gender variance. And then initiate healthy debates and open minded discussions on the issue at the college level.

However this social responsibility has been neglected by both government and social organizations for decades even after independence. Our social and political institutions still suffer from gender bias and colonial mind set of the Victorian era.

Hence we demand that efforts be made and let the governments and institutions come out with what efforts have been already done in understanding and creating an awareness about the Gender-variants issues in any field, such as law, education and medical sciences.

Generally the terms gender, sexuality and sex are taken to be the same. But they all mean different things. Sex is a biological definition and gender is the self-identity and it also means the sociocultural and behavioural perception, while sexuality refers to the sexual attraction towards a particular sex. That even within the mainstream LGBT community in India, the existence of these many genders is largely unknown.

Some forms of genders don’t even have a proper word in the dictionary and we have coined terms both in Tamil and English for a few, there are more than 20 different types of genders other than male, female and Transgender. A total positive transformation in public awareness and perception will at least take another 20 years, the government, educationists and social activists should put an effort together and the change should start from the education system. We insist that gender and sexuality education should be part of the educational system from the primary schools itself and slowly through spiral methodology enter the main syllabus in high schools and colleges with appropriate discourse value.

People are ignorant about the existence of various genders and sexuality and due to this, for over a century, women &other minority gender-variants have undergone a lot of ill-treatment and abuse. It is time to put an end to this inhuman treatment to our gender-minorities. Hence we request through this PIL that all actions that have been done so far in the field of education, culture, social awareness, medicine, research, psychology, legislation and media etc. for the empowerment of gender-minorities be brought to light, the schemes for their empowerment be brought out to public awareness so that we can take them to the gender-minorities, make them aware that the society and government respect them, make them aware of their rights and empowerment affirmation programs and also suggest improvement based on our own field study and experiences

(keep posted about this campaign here…..)

…………………………………..…………………………………..

Confessions of a fucked up mind

THE WORLD’S FIRST TRANSGENDER SITCOM!

I am promoting THE WORLD’S FIRST TRANSGENDER SITCOM. Please help support this ground breaking project so we can have a transgender created sitcom series for us all to watch. check out the FIRST EPISODE, laugh and enjoy and then simply donate some funds and/or spread the word!!!!! THIS NEEDS TO HAPPEN!

(if you know of any funders willing to fund this project with some big bucks or any media who would promote it widely then please get in touch with Raju Rage masculinefemininities@gmail.com)

Trembling Void Studios presents the first ever comedy series with a transgender lead role. And the first to have multiple transgender characters, all played by transgender actors rather than cis (i.e. “non-trans”) people in makeup.

“It’s a matter of representation, opportunity, and authenticity, and doing better than what we usually see.”

– Susan Chiv, Writer

Yesterday, Sü (Domaine Javier) was an upwardly-mobile software manager. Today she’s an out transsexual, unemployed and sleeping on her ex’s couch (Amy Fox) at the unfashionable bottom of the rabbit hole that is the East Vancouver Queer Underground. Thrown into a world of marginal living, social inequity, and quasi-legal employment, will she claw her way back to her old status? Or, to her horror, will she adapt and thrive? Set in a world changing between economies and genders, between death and life, The Switch: A Fantastic Transgender Comedy is delightfully strange, proudly crude and sharply political.

“It’s a vibrant portrayal of the chaotic, often absurd balancing acts that are our transgender lives.”

– Vanessa Tara, Writer

The Switch is Trembling Void’s first production. Shot in and around Vancouver, British Columbia, The Switch is a Canadian-made and run production. This bold and unprecedented comedy is guaranteed to have viewers saying, “Why isn’t it next week yet?” To get a taste of what everyone is raving about be sure to check out the trailer, debuting March 1st on Kickstarter at www.kickstarter.com/projects/tremblingvoid/the-switch-a-fantastic-transgender-comedy

We’re also launching a Kickstarter campaign on March 1st, so check our website at www.welovetheswitch.com for more details on how to help and how to get involved. Follow us online at twitter.com/kicktheswitch, and facebook.com/welovetheswitch for updates, videos, photos and other exclusive content! Our distribution plan includes multiple streams: DVDs, flash drives and direct downloads, stretching traditional delivery methods for lawsuit-free media.

Trembling Void Studios is based out of Vancouver, British Columbia where many great productions come from and thrive. Trembling Void makes entertainment that is unapologetically fun, punchy and opinionated. The company aspires to live in a future full of awesome. To that end, they make entertainment that moves us in that direction both socially and technologically.

A promotional gala will be held March 16th at Cafe Deux Soleil in East Vancouver. Check www.welovetheswitch.com for updates and more details as they come.

“We see it, and we see the joy in our lives.”

– Amy Fox, Executive Producer

Contact:

Amy Fox

Executive Producer

Trembling Void Studios

Vancouver, British Columbia, Unceded Coast Salish Territories

Telephone: 778.706.2369

Email: info@tremblingvoid.com

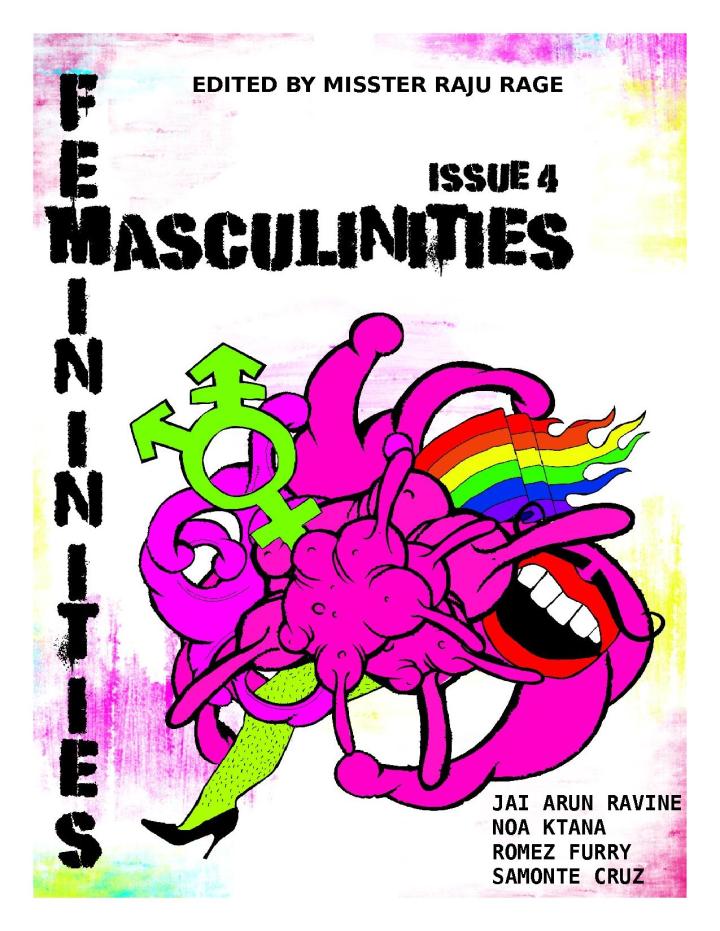

Issue 5

Cover By Lola Love

Its been a while since the last issue so this issue is surely due….

Thanks to all the contributors….you make me come alive in your words, your pictures, your meanings and expressions:

Amita Swadhin

j/j hastain

Julio Salgado and Yosimar Reyes

Lola Love

Ofelia Del Corazon

Teht Ashmani

Edited by Misster Raju Rage

Please send your submissions to masculinefemininities@gmail.com

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

POST-FEMME By Amita Swadhin

a wise friend once told me

that life is a series of coming outs.

now it’s a new year,

and i’ve made some resolutions

so, there’s something i need to tell you:

i’m. not. femme.

yeah, that’s right, you heard me.

i know, i know, there was that calendar…

but that’s so two thousand and eight.

i mean, ‘femme’ did work for me

once upon a time.

but i take it back.

i’ve changed my mind.

“i think there’s something you should know,

i think it’s time i told you so,

there’s something deep inside of me

there’s someone else i’ve got to be.

take back your picture in a frame,

take back your singing in the rain,

i just hope you understand –

sometimes the clothes do not make the [wo]man.“

time travel with me

back to 1983:

i’m five years old.

Osh Kosh overalls

dominate my wardrobe.

i get my hair cut

at a boys’ barber shop.

i buy my clothes

in the boys’ section.

spend my days climbing trees

and skinning knees,

playing Donkey Kong

and Voltron,

bossing all the boys,

taking all their toys…

it’s true – i’m a bit fey.

but that was cool, back in the day.

then comes ’86 –

a year that lived up to its name.

my father starts lectures

that last through high school:

“girls need to cook and clean.

you have to be a good wife one day.”

my guy friends stop talking to me

so i cling to my girls,

but they’ve all turned to Barbie by then.

two years later,

i cry when i get my first training bra.

they aren’t tears of joy.

i ask my mother for a razor and makeup

soon after.

the choice is clear:

fit in, or face laughter.

or worse.

fast-forward to 1995 –

by then, i have mastered makeup

but so did Freddie Mercury.

so did Prince.

by then, i am over it.

all of it.

i cut off all my hair,

and it feels right.

look, i never wanted to be a boy.

but i never wanted to be a girl, either.

i wanted something better:

i wanted liberation.

i found ‘queer’

and then i found ‘femme.’

at first, it feels right:

claiming pink

while breaking all the rules.

there is power in being pretty

while being subversive

and i wanted it.

no one warned me that

it was a trap.

i learned the hard way.

1999: my first date with a woman

this has been a long time coming.

it’s going well until she says

“you are really confusing! and aggressive!

opening doors,

pulling out chairs,

trying to split the bill.

i thought you were femme!”

i am bewildered.

it’s mostly downhill from there.

i shave my head

and buy men’s clothes

and suddenly, all sorts of femmes

who have never noticed me before

wanna get my number.

meanwhile,

the trans guy

who i’ve been talking to

says

“i’m not sure what you’re tryna do,

but you’ll always be femme

no matter what you wear.

i mean, look at you!”

i grow my hair again, and get a new girlfriend –

a femme in a previous love life.

she screams

“were you trying to embarrass me?”

when i wear sweats

to dinner

after a 10-hour work day.

a ‘high femme’ asks

“what kind of femme wears hiking boots?!”

when she hears i’ve been walking out in the desert.

a trans man i have been dating says

“i really need to be with a sweet girl.”

as he breaks up with me.

i thought we wanted

alternatives to the cops.

so what’s with all the

community policing?

when did the rules

for ‘femme’

and ‘straight girl’

start to sound so much the same?

let me be clear:

the only type of ‘femme’

i’m invested in being

is the kind that ends in I-N-I-S-T.

my gender is more layered

than the eyes can see.

and yeah, i see you

wanting to label

my hair,

this dress –

so feel free.

i’m a performer.

i’m just doing me.

but i wanna know –

what are you doing

to work for liberation?

how we all gonna get free?

we have to move

beyond the binary.

Amita Swadhin is an LA-based, NYC-bred educator, activist, storyteller and shapeshifter. She is the coordinator and a cast member of Secret Survivors (a theater project she created with the award-winning NYC-based Ping Chong & Co. featuring survivors of child sexual abuse telling their stories), a performer with and co-producer of The Sugaran Tour, and co-host and co-producer of the weekly radio show Flip the Script on KPFK-LA. You can read more at www.amitaswadhin.com.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

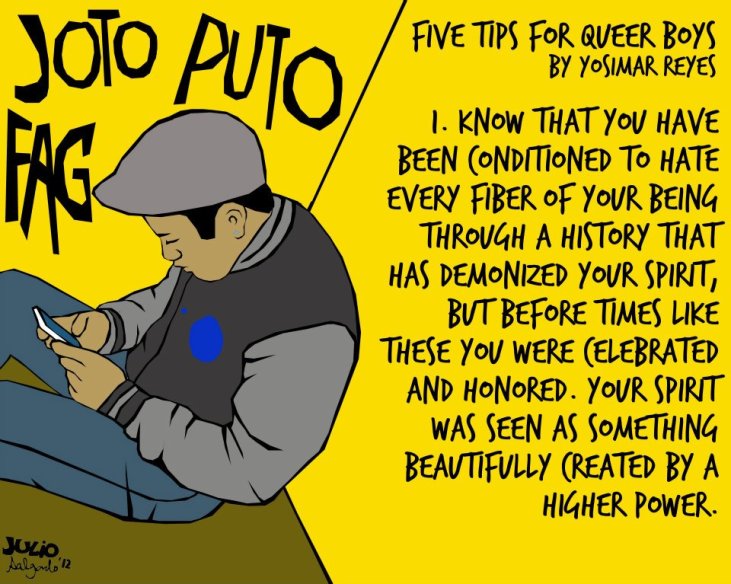

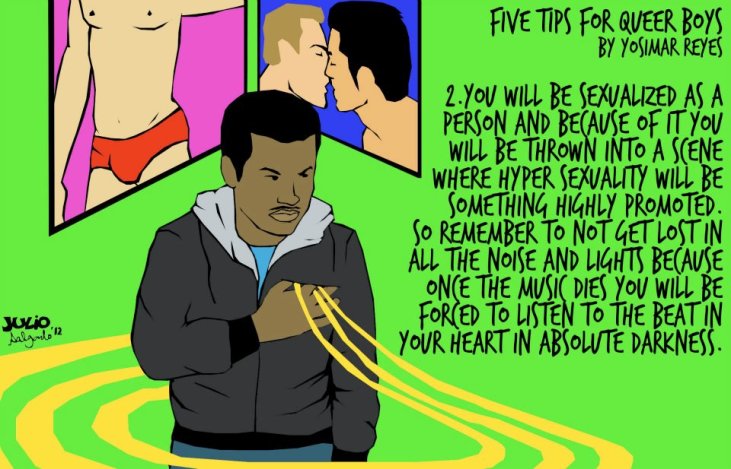

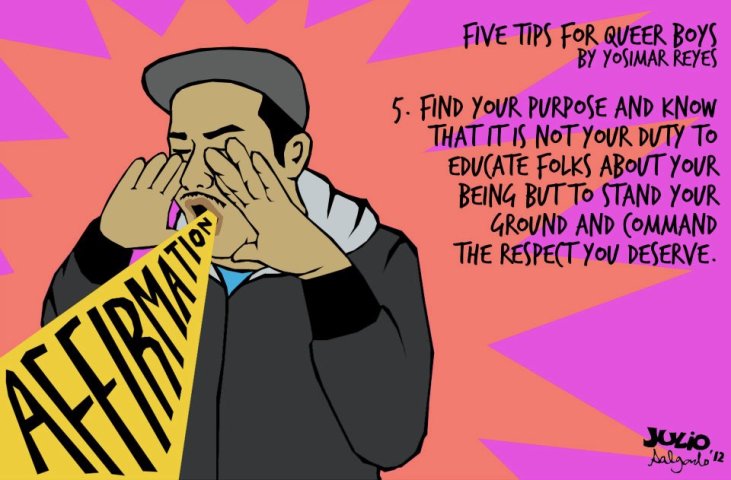

Five Tips For Queer Boys by Yosimar Reyes

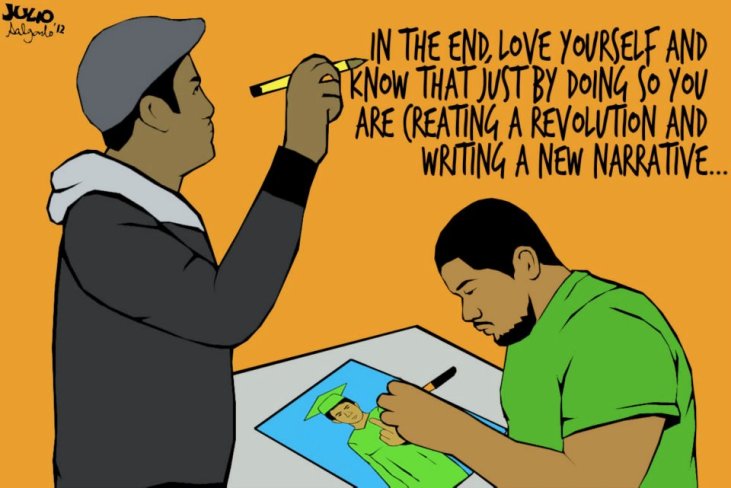

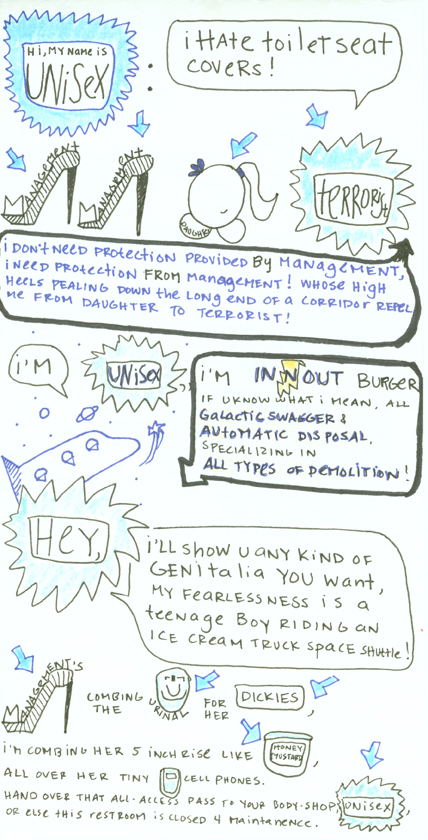

This set of illustrations, is a collaboration with the amazing Julio Salgado and Yosimar Reyes.

Julio Salgado is the co-founder of DreamersAdrift.com. His activist artwork has become a staple of the DREAM Act movement. His status as an undocumented, queer artivist has fueled the contents of his illustrations, which depict key individuals and moments of the DREAM Act movement. Undocumented students and allies across the country have used Salgado’s artwork to call attention to the youth-led movement. Using the phrase “I EXIST” within his artwork, Salgado wants to use art as a way to combat words like “illegal” and “alien” that tend dehumanize undocumented immigrants. Salgado graduated from California State Universitiy, Long Beach with a degree in journalism.

From the Mountains of Guerrero, Mexico comes Yosimar Reyes, a Two-Spirit Poet/Activist Based out of San Jose,CA. His style has been described as “a brave and vulnerable voice that shines light on the issues affecting Queer Immigrant Youth and the many disenfranchised communities in the U.S and throughout the world.” Yosimar’s distinct style has managed to get him to perform form the Bay Area to New York City (always Representing East Side San Jose and his beautiful Mexico).

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

“Dear Internalized Biphobia: An Open Letter To The Ugly Beast Inside Me” by Ofelia Del Corazon

Dear internalized biphobia,

We’ve never had a healthy relationship and I am glad to say we are drifting apart. It’s been a long time since you showed when I was eleven. When I went to mass where the priest said that birth control and abortions and homosexuality were all equally bad. At that point I knew I liked boys and everyone said that was okay, but I was just starting to figure out that I liked girls too. That feeling I got when I liked a boy was the same feeling I got when I really wanted to be a girl’s friend. Like her best best friend. That’s when I started praying at night that I would wake up and my bisexuality would be gone.

But it never worked and my bisexuality, and you, biphobia remain inside me. Still though it wasn’t all bad. By the time I was thirteen I had reasoned that I was only half gay. I still had the option of squashing my squashing my feelings for other girls and I was thankful that I liked boys at all.

Thankful that I could at least, openly experience part of my sexuality… I did think boys were hella hot. Well, some of them. Often they were the girlie ones. With big pretty eyes and full mouths and long hair. The sweet shy ones who would let me do anything to them (like dress them up in my clothes) and would do anything for me, like steal hair dye and lipstick for us both or submit to being made to march around town in my thigh high stockings and lacy under things. I told my first boyfriend that I was bisexual and later he confided in me that he was bisexual too.

A few girls came out as bi when I was in high school but everyone laughed and talked about them behind their backs and I did it too. I remember my best friend said that “They do it to get attention.” That it was ‘trendy’ which was the ultimate insult among my group of outcasts and theater freaks. I wanted to tell her so badly that I was bisexual too. There was nothing fun or exciting about knowing that you were going to burn in hell for all of eternity. I was too afraid to say anything. She already refused to undress in front of me perhaps because I could never stop looking at her boobs.

I went to high school in a mostly Latino rural farming community and I had two secret girlfriends during the time. We were so secret; we were secret from each other. We would spend the night at eachothers’ houses and lie tense and quiet before becoming overwhelmed with teenage lust groping each other, humping and kissing and fucking quietly and sloppily all whilst pretending to be asleep. Which, if you’ve never tried to pretend to be asleep while fucking, it is sort of like pretending to be a zombie whilst fucking: it’s hard to do and not very sustainable. It also kind of makes you a bad fuck by default.

We didn’t hold hands or kiss in public. We just waited until it was time to sleep and then fucked in the dark then pretended like it never happened the next day.

By the time I was seventeen I was firmly convinced I was a lesbian no longer bisexual, until, I met a boy, well, actually a man on the Internet. I told him I was a lesbian and his acceptance validated my queerness for the first time. He was deeply flattered to be my grand exception. I agreed to move to southern California but only if I could date girls too.

Around the time I began to learn about feminism I realized what a misogynst assshole my boyfriend was. I moved out of our apartment the and into an environmentalist co op. I swore to all the hippies that I was a dyke although I would still bed men in secret.

I started dating a butch woman who asked me casually on our first date “When was the last time you had sex with a guy?” I felt my queerness under attack. I was threatened; it had been about two days. “Two years!” I lied, not knowing if that was long enough, my heart beat fast but I relaxed when she smiled. “Oh, cool. I’m gold star, myself.” she grinned, bragging. I pretended like I knew what that meant.

Only my roommates at the hippy co-op new my shameful bisexual secret (they saw the parade of men that came in and out of my room) and eventually they confronted my gold star girlfriend about it. “We’re poly.” She snorted. “And it’s not like she fucks every single guy that comes over!” but it was true. That’s pretty much all I was doing with guys at that time and at the end of it all I’d throw their clothes at them and growl and snarl and swear that if they ever told anyone I fucked them that they’d never get to fuck me again. It worked. My secret was safe. For a time.

One thing remains constant: I like to fuck hot people. It’s only been a few years since I have begun feeling all right about calling myself a bisexual. I’m not sorry to see you go internalized biphobia go, we’ve fought long and hard: like two lovers locked in a struggle, who get too tired to fight or just realize how much they love each other and began to fuck.

I wonder if you’ll ever be gone completely, biphobia. I wonder what it would be like to live without you.

With love and forgiveness,

Ofelia

www.mommyfiercest.com and also twitter.com/mommyfiercest

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Oh tower made of cloth. I was meant to be your lover. Correlational femme to your female he.

An inverse mirroring. A code toward arrangement or

orgasm. Enactment of the identity and the identity itself. This is document of the tractions. A

thrum-rosary. I read you

by transposing. You read my by capsizal. My own reactive body burgeoning. My hem line to your hemlocks. An etiquette of scorching

musculatures. Glandular and groin oriented ephemeral. Opening

what was ever waiting to be awash.

We fill a gong with our come. With our co emissions you make shapes on my forehead. Chivalry that is not a fantasy but imbued. A joy

that is dependent on depth. Like a mantra of new syllables. My torqued adam who mines me by way of shared atoms. “I will never misuse you.” This is a way to reverse callouses that prior to you have stayed. I longed for your short hair in my grip. For how we look like

else. How we feel like sweltering leaves can be felt from within.

The subversion of singular identity for the sake of

deifying one’s lover. To infiltrate me you braid my hair on the steps in the rain. Here tears are communication more than words are. Enactment as recollection

by surges in the lace wings. A stinging. We are adrift in a cave where bodies of flight engage erratic wafting. Inexorable pleasures

near a tributary that smells like pepper. Prepare me through potash. Through promises of more than

approximate. To fill the moat with ______. This grander is making us

whole by action. You read to me to bring the night closer. You float your cock inside of me and I feel us as both ephemeral and physical. As an inexhaustible length

of scroll.

j/j hastain is the author of several cross-genre books including long past the presence of common (Say it with Stones Press), trans-genre book libertine monk (Scrambler Press) and anti-memoir a vigorous (Black Coffee Press/ Eight Ball Press (forthcoming)). j/j has poetry, prose, reviews, articles, mini-essays and mixed genre work published in many places on line and in print.

http://www.jjhastain.com/

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

My Statement Against Intimate Violence

It is not okay to tell your partner that no one else will love them.

It is not okay to tell your partner who is trans-masculine identified that they are not ‘man enough’.

It is not okay to say to your partner, who is transgender, who has multiple gender identities that they have a ‘multiple personality disorder’ and criticise/scrutinise their gender. It is not okay to not use incorrect pronouns with your partner to other people when they have requested you to use specific pronouns when referring to them.

It is not okay to joke/laugh about your transgender partner being read as a child/young person/underage with your friends in front of or even behind your transgender partner‘s back, even if your partner has joked about it with you personally and privately.